|

Jazz guitar mixes very nicely with congas and timbales, it turns out. Though the recorded canon of guitar-centric Latin Jazz certainly has its moments, full albums of guitar-driven Latin Jazz have actually been fewer and further between than one might expect. When the album "PARTING SHOT" was released in 2011, it was the first Latin Jazz album led by a guitarist since Grant Green's 1962 Blue Note disc, The Latin Bit. Now Steve Khan, the guitarist behind "PARTING SHOT," has released an exquisite follow-up with "SUBTEXT." on Mike Varney's Tone Center Records in the U.S., 55 Records in Japan, and ESC Records in Europe. Joining Khan on "SUBTEXT" are Dennis Chambers on drums, Rubén Rodríguez on bass, Bobby Allende on conga, and Marc Quiñones on timbal, along with a slew of special guests including flügelhornist Randy Brecker, keyboardist Rob Mounsey, vocalist Mariana Ingold, and Gil Goldstein on accordion. For those unfamiliar with Khan's prolific recorded history in jazz, and the Latin Jazz with which he has long been associated, the guitarist has both followed and broken with jazz tradition in numerous instances.  His use of Marshall speaker cabinets in the studio might be common among jazz fusion players, but Khan's primarily more traditional jazz has mostly avoided fusion's rock-ish excursions -- his jazz leanings lack the overdrive and attitude of, say, the music of Jeff Beck's Wired or Blow by Blow. Yet show up at a Khan session and you'll definitely hear those Marshalls pumpin'. His use of Marshall speaker cabinets in the studio might be common among jazz fusion players, but Khan's primarily more traditional jazz has mostly avoided fusion's rock-ish excursions -- his jazz leanings lack the overdrive and attitude of, say, the music of Jeff Beck's Wired or Blow by Blow. Yet show up at a Khan session and you'll definitely hear those Marshalls pumpin'.And while his musical career has largely stayed true to traditional jazz instead of going the jazz-rock fusion route, he hasn't entirely avoided paying tribute to the rock heroes he first set out to emulate as a Southern Californian teenage drummer in the 1960s. Khan has recorded jazz tributes to both the Beatles and the Beach Boys at various junctures in his decades-long music career. He has worked with Steely Dan founder Donald Fagen, and has repeatedly recorded and toured with Allman Brothers Band percussionist Marc Quiñones -- a highly regarded salsa percussionist who has been a full-time member of that Rock and Roll Hall of Fame band since 1991. But it has always been jazz, and much of it Latin-tinged, that has been Khan's specialty. In recordings dating back to the 1970s, and in working with esteemed players such as Steve Gadd, Michael and Randy Brecker, Billy Cobham, David Sanborn, Tom Scott, Ron Carter, John Patitucci, Jack DeJohnette, and simply too many jazz masters to mention. Khan teamed with Larry Coryell in 1974 to form one of the first jazz guitar duos, and toured with Weather Report founder Joe Zawinul in his 1986 version of the band, Weather Update. The New York City-based guitarist grew up around the music industry -- his father was famous songwriter Sammy Cahn ("Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow") -- and was influenced early on by jazz guitar legend Wes Montgomery, who knew Khan, and found himself regularly deflecting the younger guitarist's questions. In this exclusive Guitar.com interview Khan spoke with us about Wes Montgomery, recording loud, and about his very robust and informative website. The guitarist also delves into the state of Latin Jazz, and the guitar's place in the genre; recommends several great resources for musicians (besides his website, which is full of free lead sheets transcribed by Khan himself); and tricks of the trade learned from jazz masters such as Joe Zawinul and drummer Steve Gadd. Adam St. James "GUITAR.com" [Guitar.com]: Hi Steve, how are you? [SK]: Thanks Adam, I'm doing great! [Guitar.com]: From looking at your website, you appear to be a very meticulous person. You have posted a ton of great information for guitar players. [SK]: I was one of the last guys to even get a computer, and I was so far behind everything and everybody else. I don't think I got my first computer until '98, and I remember, not too long after that, I happened to be up at Michael Brecker's house. We were doing something together, and he said, "Come here, I want to show you something," and he showed me his website. And he said, "You have to have one of these. You would love this!" So coincidentally at the same time, keyboardist Rob Mounsey had gotten a fan letter from a guy who liked a record that we had done together in '98 called "YOU ARE HERE," and, this wonderful guy, Blaine Fallis ]who lives near Houston, TX - and to this date, Blaine and I have never actually met face-to-face!], offered his services to build a website for me. And so I sent him boxes of photos and CDs, and everything else under the sun too. After some trial and error, we came up with a look that we both liked. As the years went by, I took over the bulk of the work. I felt guilty always asking him to make the smallest of changes to pages at the site, and so I learned how to do the html myself. I guess everybody else has these flash websites now, but mine is really meant for people who are actually sitting at a computer with a real screen, and who enjoy reading. The people who actually explore my site, and enjoy reading the pages, really love it. [Guitar.com]: Your website is certainly a wealth of information, with all the lead sheets that you've transcribed, and so much jazz history, and awesome instructional material. [SK]: When I was starting the site, I looked at what was out there on the web, and two of my webpage role models at that early time were Michael Brecker and Peter Erskine. Then I went to all these other pages, and saw things I would never want to do, and, some other things that I thought I could give an interesting take on. I wanted to try to make all of my lead sheets of my original tunes, and some arrangements, available to everyone. There are pages that contain a tune that I might have recorded, but it is just my arrangement of, for example, a Randy Brecker tune.  But if you compare it with other sites, there's a difference in philosophy. I know many excellent players on various instruments who don't offer anything without selling it. For me, I feel that if a couple hundred people visit the site, and one guy actually prints out one of the lead sheets, and then, goes to rehearse it with his band, I'm thrilled with that. You just want to keep the music alive, and for me, I'd rather make it as easy as possible for somebody to access the music, and then play it, rather than making a few bucks. People say, "You're really stupid, you should be selling everything," but I find it really hard to do that.

But if you compare it with other sites, there's a difference in philosophy. I know many excellent players on various instruments who don't offer anything without selling it. For me, I feel that if a couple hundred people visit the site, and one guy actually prints out one of the lead sheets, and then, goes to rehearse it with his band, I'm thrilled with that. You just want to keep the music alive, and for me, I'd rather make it as easy as possible for somebody to access the music, and then play it, rather than making a few bucks. People say, "You're really stupid, you should be selling everything," but I find it really hard to do that. [Guitar.com]: Speaking from experience, I can tell you that sometimes selling instructional materials or books or DVDs online can be more hassle than it's worth. [SK]: The whole book world is such a strange place to me. I've got four books out there. Two are transcription books that I did ages ago: a Wes Montgomery book, and a Pat Martino book, that are considered by some to be the bible for those two incredible and historic players. And then, I have my own two concepts books, "CONTEMPORARY CHORD KHANCEPTS," and "PENTATONIC KHANCEPTS." It's really strange, but my two books of my own materials actually outsell my transcription books three to one. I'm not sure how this happens, but I'm glad that they sell anything. A lot of people think, just because you have a book out there, that you're making a lot of money from it, when in truth I barely make anything. And if you consider all the man hours that go into making it happen, you're never compensated for that. Never ever!!! So I look at anybody who has written a book, and I know it was a work of love, more than anything else. I don't think there's a publisher who could really pay anyone for the time it takes to actually do all the work. [Guitar.com]: I agree. So you've written out and posted all these great lead sheets and your analysis of each tune, whether it's your own tune, or something by Wes Montgomery or Pat Martino, or all the others you've covered. Your analysis on each song is so detailed, it's really very cool. And I know it's a labor of love, to a large degree, [SK]: Yes, I think that for the people who are studious types, I'm really trying to demystify things, and break it down into an understandable language, where somebody could take that information and convert it into their playing right away. Sometimes people don't want something handed to them like that, they want to believe everything is so magical. That doesn't mean that, just because I analyze something in a particular way, it is the way the actual player -- like Wes or Pat -- relates to the song and the changes. I think when you're taking something that was played by someone else, and trying to make sense of it, for yourself or another person, you want to choose a way that really makes sense, and simplifies it so that someone can take advantage of it. Especially where jazz is concerned, there's a sense that everything happens by magic, and there's no rhyme or reason to anything, it's just this magical stuff that's happening. That's not necessarily the truth at all, as I view things. Guys really study and work hard at their craft. Even the guys who are intuitive players, guys who don't read music, who don't know anything, or very little, about music theory, but their on-the-job training gave them a Ph.D. in music improvisation. Wes Montgomery didn't read, nor George Benson. But how can you argue with guys who play that great? In the end, it doesn't matter. They just hear it. But that's not what works for everybody. [Guitar.com]: You were a drummer in your teens and you just played by ear, but when you switched to guitar you decided to get more serious and study. [SK]: True. In the early '60s, around the time of the Beatles, everybody wanted to be in a band. Some of my friends had guitars, so I thought that the drums looked the easiest. So I assembled a kit from spare parts, and I guess I was just banging away. I had lofty ambitions, but I really didn't get it. My father sent me to take drum lessons, and I remember walking into my first lesson, and it was this cold little square room, and in the middle of the room was a little wooden practice pad with a black rubber circle on it. And I'm looking around going "Where are the drums?" And when the teacher came in he said, "The first thing you have to do is learn the rudiments, learn stick control, and have an artful way of playing. Everything starts from the snare drum." And I didn't get it. And I said to myself, "Wow, this is so far away from what I want to learn." It wasn't until 10 or 15 years later, I remember sitting in the studio one day -- by then I had been a guitar player for some time, and yes, I really worked hard to study, and to be a better musician. Or be a musician, period. I was sitting in the studio that day, and Steve Gadd was there, waiting for his drums to arrive. There was nothing there except a snare drum. So we were sitting around, and all of the sudden he starts to play the snare drum, and he's playing all this ridiculous, amazing, musical stuff. And suddenly this huge light bulb went beaming over my head, and I realized, "Oh my God, that's what my drum teacher was talking to me about!" But way back then, I just couldn't see it. I didn't get it!!! I sat there and realized, that's why Steve Gadd is so great. He has this beautiful control over every last stroke and detail. By then, I had been playing with him for a long time, but I never looked at it that way. There he was sitting with just the snare drum, nothing else. So sometimes you're ready to learn, and you know what to do, and sometimes you're just lost, and you don't get it. And that's where I was as a drummer. Needless to say I'm happy to not be a drummer now. I think my recordings show that I have a great love and respect for the drummers who play on them. [Guitar.com]: And you've played with some awesome drummers. And then there's the whole Latin Jazz thing, and the percussive elements of that. Where did your love of Latin Jazz come from? Was it something that you heard growing up that sent you in the Latin Jazz direction? [SK]: The truth is, yes. In the liner notes to "PARTING SHOT," the CD before my new album "SUBTEXT" -- I wrote the story of my relationship to Latin music. Of course, there are always space problems with a CD booklet. There is a word count limitation. My liner notes are pretty much the true story, though I left out the childhood part. I always remember that, in the '50s, the United States went cha-cha crazy. All the grown-ups who liked "Leave it to Beaver," and "I Love Lucy," all the shows that were on TV in black and white at the time, in those households, and I don't know how it happened -- but there was this cha-cha craze for the parents. My father was a famous songwriter [Editor's Note: Steve Khan is the son of legendary songwriter Sammy Cahn]. He loved to listen to his own songs at home all the time. And all the sudden, he started bringing home recordings by all the great singers, but now singing some of his songs as cha-chas. I remember Peggy Lee did one of my father's songs, "Come Dance With Me" as a cha-cha. That's probably my first recollection of hearing a cowbell. On the other hand, Mickey & Sylvia's "Love is Strange" was a big hit in 1956 and there was plenty of cowbell on that!!! Suddenly, it reached me in a way that's still really hard to explain. I just had this response to it, and it stayed with me.  It's really funny: As my life as a musician unfolded, there was always a relation to Latin music. Some of it was by accident. I remember when we had this band in the early '70s, Count's Rock Band, and there were three Steve's in the band: saxophonist Steve Marcus, Steve Gadd and me. Keyboardist Don Grolnick, and Will Lee were in the band too. We had been playing some of these tunes of mine for quite some time before that band, but now they were going to take on another shape, as Steve Gadd was going to play them. Suddenly he started playing all this cowbell stuff that he would do on occasion on various other recordings. Perhaps people associate that with some of the early Chick Corea records that Steve played on?

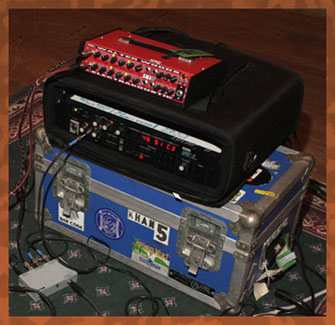

It's really funny: As my life as a musician unfolded, there was always a relation to Latin music. Some of it was by accident. I remember when we had this band in the early '70s, Count's Rock Band, and there were three Steve's in the band: saxophonist Steve Marcus, Steve Gadd and me. Keyboardist Don Grolnick, and Will Lee were in the band too. We had been playing some of these tunes of mine for quite some time before that band, but now they were going to take on another shape, as Steve Gadd was going to play them. Suddenly he started playing all this cowbell stuff that he would do on occasion on various other recordings. Perhaps people associate that with some of the early Chick Corea records that Steve played on? So the Latin element that started back then just continued as I began to record for Columbia Records and I always made certain that there was at least one tune like that, a Latin-oriented piece. And then, suddenly, when I was dropped by Columbia in 1980 - along with about 50 other artists at the time -- I was really lost for a time. I pared down all my gear because, simply put: I hated the way I was playing, and I hated my sound. I just went back to something, that for me, was really pure and simple. A Gibson 335 into a little Fender amp with a little reverb on it. That was it, end of story! But the beginning of a new story!!! In 1981, we started a band, which became known as Eyewitness, although, it really wasn't the name of the band. It was with bassist Anthony Jackson, Steve Jordan, and percussionist Manolo Badrena. We had these tunes, and again, Steve began playing the cowbell on a couple of them, and suddenly it was like we were playing this strange Latin music, although it had very little to do with the clave, and all the other traditional elements. It was instinctive to us that this was the direction that some of the music was taking. That was between '81 and '85. As time went on, Manolo would tell me, "You know, the people in the Caribbean and South America, they love these records. For them it's changed the way they play certain kinds of music now." And I said, "You're kidding?!?!" And he said, "No, I'm dead serious." I didn't believe him at the time, until I started meeting many musicians from Central America and South America. It was really gratifying to me that was, in fact, how many of them perceived those records. As the years went by, I never really let go of it, but as we come to the present, my desire to try and do it "the right way," or, in a better way, than I had been doing it, is really at the forefront for me. I made sure that I had some of the best players possible to play it, and had the music that fit with it. When I did "PARTING SHOT," which we recorded in 2010, and it came out in 2011, I hadn't been really thinking about this, but when I looked over the landscape of Latin music, and it's relation to the guitar, that album was the first record of really serious Latin music, led by a guitarist in 50 years. The last record, where it was "wall-to-wall Latin music," was Grant Green's famous album, "THE LATIN BIT" for Blue Note in 1962. It was remarkable that I was the only guitarist who was operating in this particular musical zone. That doesn't mean that other guitarists haven't done a great track or two, where there was conga, timbal, and all the necessary instruments to make it Latin music. Of course, there have been those tracks, but not entire albums. So that's the long answer, but when you get to my age, there's not a short story to anything! (Laughs) [Guitar.com]: Why do you think guitar players haven't led an album of this music in so long? There's a history, of, at least Brazilian jazz guitar playing... There's a history of guitar in Latin music. [SK]: I think that Brazil operates in its own wondrous world of Latin music. It's very different. The drums, conga, and hand percussion involve such different sounds than in the Latin music as we think of it, for example, in salsa. They are two distinct areas of the genre. But I think that, if I was to take your question in a particular direction -- the fascinating thing to me is, especially since the Internet, that I can now communicate with many wonderful musicians, all over the world, that I might never even meet personally. I communicate a lot with musicians in South America, Central America, the Caribbean, and Spain, so I'm pretty familiar with many incredible Latino guitar virtuosos. But virtually all of them want to play fusion music, in some form, with some kind of overdrive, or they want to be in this other area of the jazz world playing more abstract music, which usually means trio: Guitar, acoustic bass, and drums. The problem with doing that, even here in New York, is, where do you find drummers who can do that? That's the age old question anywhere you're playing music. The band is only going to go as far as the drummer can take you. Here, for years, everybody was looking for an Elvin Jones, or Tony Williams, or Roy Haynes, or Jack DeJohnette, or Paul Motian -- that generation of great, great players. There will probably never be another Elvin Jones. I don't know if we'll ever see somebody like that again.  But it's really hard to play hard swingin' music in the abstract, and get it to feel right, although I think that many Europeans do this beautifully. But it's really hard to play hard swingin' music in the abstract, and get it to feel right, although I think that many Europeans do this beautifully. I guess the point is that, if you ask me, "Why don't all the great Latino guitarists use the rhythms and sounds closely connected to most of their own cultures?" Honestly I don't know, but they seem to be more fascinated with fusion music, which I think is more closely connected to rock, and musical sounds that are familiar to them, at least on the guitar, which probably goes back to their childhood. [Guitar.com]: Can you recommend a really concise resource of the various Latin rhythms a guitar player could listen to and learn from right now? [SK]: Yes, I have some book that have served as my bible for trying to study Latin music, and to better understand it. My favorite book of all of them is from the Drummers' Collective series, Manhattan Music Publications. The name of the book is "AFRO-CUBAN RHYTHMS FOR DRUMSET," by Frank Malabe and Bob Weiner. This book -- and it comes with a CD -- doesn't have anything to do with guitar. But if someone really wants to understand the rhythmic components of Latin music, the clave, the various patterns that the conga, timbal, and the bells are playing, I think that this is the greatest book. Everything the percussionists were doing used to be a complete and total mystery to me. It didn't make any sense. But once I started studying this book, and making little marks on certain pages that had the information that I felt that I needed to know, I started to memorize it. In time, I finally felt like I understood it. Now, I get it, and I still feel like a humble student when I'm around players like Marc Quiñones, Bobby Allende, and Rubén Rodríguez. So that book is really an incredible! It also has a couple of chapters at the beginning about the history of the merging of the African and Latino cultures. It really gives you a nice overview. The book is only about 80 pages. [Guitar.com]: It's still in print, from Alfred. I actually have a copy. [SK]: Where books are concerned, that's my absolute favorite book. The other resource I like is Marc Quiñones' CD of samples for LP Latin Percussion, but in the front of the CD, before he goes through all the instrument samples of every Latin percussion instrument, he performs nine traditional Latin grooves. First he plays it with all the parts together, and then he breaks it down into, "Here's the conga part, alone," "Here's the timbal." It's so great. You can hear individually what every instrument is doing. They do that on the CD for the Frankie Malabe book too. Oh, I almost forgot, there's one other book, again more related to the drums and bass, it's by Robby Ameen and Lincoln Goines, it's called "FUNKIFYING THE CLAVE." The good thing about this one is that you have the bass too, so you have a harmonic center. This book is excellent!!! I learned a lot from those three resources, but mostly I learned by going out to clubs, hearing the music, and sitting with guys who became friends of mine, and asking all the stupid questions that I wasn't afraid to ask. I guess I've never been afraid to ask stupid questions. This is what I used to do when I would to go to see Wes Montgomery play.  I used to ask the eternal student's question: "How do you do that?" And of course, the answer was always, "I don't know, I just do it." I used to ask the eternal student's question: "How do you do that?" And of course, the answer was always, "I don't know, I just do it." When I was a kid, I would to go see him play, and he was really, really nice to me. He was a really sweet man. I used to think, "He's not telling me something. There's something he knows, and he's not telling me, because, how could anybody just do that?" Then, when I got older, and I started to play - and please believe me, I don't see myself as a Wes Montgomery in any way, shape, or form -- but there does come a moment where you're playing live somewhere, and you're not thinking about anything, you're just playing, and some kid comes up to you and says, "How do you do that," and your answer is, "I don't know, I was just playing. I just do it." Then you realize that Wes wasn't hiding anything. When you are really playing, and in the moment with your bandmates, you're not supposed to be thinking about anything. You're just in the flow of the music, and you're just playing. It's different if somebody brings you a CD that you played on, or as you see on my website in my transcriptions and the songs that I've analyzed, it's different when you're listening to that, because it's something that is preserved from a moment in time, and there's a chord, and there are notes, so you can analyze it. It's not a mystery once it's there. But live, you'd have to go back, hear it again, and then say, "OK, I hear what you're referring to. In that moment, what he played comes from such and such." But, of course, nobody does that. [Guitar.com]: You would have to have a recording of what you just did, and you'd have to watch it and think back on it and say, "Oh, I see what I did." [SK]: Yes, because there are tunes, there are chord changes, and in the end, we are all negotiating these things. That aspect, it's only a mystery if you're playing a tune, and nobody knows it except you and the band. I think if one was willing to do it, you could explain anything. [Guitar.com]: Well, your great new album, "SUBTEXT" is full of wonderful new Latin Jazz. It's your first album in three or four years. Where did these tunes come from? What were you setting out to do with this album? [SK]: "PARTING SHOT" and "SUBTEXT" are joined at the hip, conceptually. I really thought that "PARTING SHOT" was going to be the last recording I was ever going to be able to make, because I have been self-financing these recordings from my savings. I've been doing this for a long time. I think I've self-financed nine of my records, which is a lot. And only one of them did I ever got the money back, and that was the first one, my solo acoustic guitar album, "EVIDENCE" from 1980. I think it cost me about $6,000, and I was having a panic attack about that! Since then, it's been downhill, financially speaking!!! (Laughs) . I reached a point where I felt, if I tried to make another recording, I would be putting, my life savings at risk, in the event that something really bad happened to my health. I don't want to be a burden to my son or anybody else. I wanted to be responsible. I felt like I had gone as far as I could go. The record business is dying. Nobody really has a record deal anymore, the writing is on the wall. So with "PARTING SHOT" I made the best record I could, and I just let it go. I wasn't sure where my life was taking me. Then, around the holidays of 2011, I woke-up one morning, and I felt this little bump in the palm of my left hand. I thought, "What the hell, that wasn't there before, what is that?" It didn't hurt, it was just something that hadn't been there before. So I consulted with some guitarist friends about hand specialists, because guitar players know about hand specialists -- most guitarists have had a bout with carpal tunnel or something similar -- so I got the names of a few hand specialists, and at the time, the doctors who were recommended to me did not take my insurance. So I had go to see a doctor on my network, and I thought he was going to tell me something like this, "It's just a little cyst, let me stick a needle in it, drain out the fluid, and it will be fine."  That's what I thought was going to happen. But when I walked in there, he took one look at my hand, and said assuredly, "Oh, this is Dupuytren's Contracture." That's what I thought was going to happen. But when I walked in there, he took one look at my hand, and said assuredly, "Oh, this is Dupuytren's Contracture." I knew what it was because ironically, at the time, there had been some commercials on TV where you saw this old guy -- like me -- with gray hair, and he's painting a wall in his house, and then, it shows that he can't get the brush out of his hand, because his fingers have contracted in, and his hand won't open up. The commercial was about a medication that might work. It has since been removed from circulation!!! So now, I had this diagnosis that, for a minute, paralyzed me with fear. I could see that, if the fingers on my left hand curled in, and I can't open them, how the hell am I supposed to play the guitar? I really saw the end of everything in front of me. When I turned 65, and went on Medicare, and could then go see any doctor I wanted to see, this time I arrived with the proper questions. After I went through all kinds of tests, I asked the doctor, "In your opinion, if I decided to make another recording, do you believe that I would have at least one year before anything bad is going to happen to me?" And he said, "Based upon what I see, yes, absolutely. What I see is the beginning stages, and this is a very strange affliction. You could stay exactly as you are now for the rest of your life, and nothing happens. Or, it could happen tomorrow. No one really knows." So I felt really great about what he said, and you know the jokes about money, "You can't take it with you when you're dead." So I said to myself, "I've got to do this record, because if I don't make another recording while I can still play at a reasonably high level, I would regret it for the rest of my life." And that's why I did this record. Every recording you make means a lot, but this record means so much to me, because, for all I know, I might never have done it at all. So, unlike "PARTING SHOT," where you see there are 10 tunes, and I wrote seven of them, as I'm a slow writer, here I decided to interpret pieces that I've always loved. I had three tunes that I did finish writing. All the songs that I chose to interpret fit into the Latin Jazz format, and now I was able to do it. So that's how "SUBTEXT" came into being. [Guitar.com]: I think if you were having any fearful thoughts about your condition while you were recording, the album itself seems very happy and joyous in many regards. [SK]: You know, it's funny what happens when people try to put a descriptive word or phrase on music, or a film. Over time, after the release of any recording, you collect some reviews, or you get emails from friends and fans, and they'll say what they think of that album, of that music. But I think the only word that bothers me the most is when someone will say or write, "Yeah man, your record's really nice." To me, there's nothing nice about it: We're playing hard! We're playing loud!! Just because I'm not playing with an overdrive sound, that does not mean we're not playing hard and loud. We are!!! So it's strange to me, but I think there is also this perception, and I guess I get it -- the "happy, joyous" thing. I think that, in some subliminal way, this is how people perceive Latin music. [Guitar.com]: Well, yeah, maybe.... So much Latin Jazz sounds like everyone is dancing and having a great time. [SK]: When people begin hearing the album, people would write to me, and say, "This is the perfect summer record, I can drive with the top down in my car." And the next thing I think that they're going to say is that: "It makes me wanna go and have six margaritas." I don't know. It's fascinating how often this happens. I think that the other thing, and I've been writing about it on the website, is that we live in this really strange time, where how people listen to music is changing - certainly from anything that I ever knew. I feel like I'm one of the last guys -- and I'm talking about musicians too - who actually owns a real stereo! By that, I mean having a powerful amplifier and speakers. Most guys listen to music when they're driving in their car. Obviously young kids are listening on their iPods and cell phones. For me, the audio part of production, of making a record, is to try to make the most beautiful sounding audio presentation you can make. And that's a lot of hard work, and when you're listening to the music, you are hearing it in a very physical way. So when somebody writes strange things about the recording - it's really obvious to me that they were either multi-tasking, and doing five things at the same time while they were supposedly listening, or they had the CD on at a dinner music volume. And that's not what any of the records I have made are about. To me it's physical music, and as loud as you might play Jimi Hendrix on your stereo -- or whatever is the most powerful rock band you ever heard -- to me, it's the same thing. It's in your face, physical music. But one can't control how somebody is going to listen to it. I don't know if you experience this, but for me, I see this all over the place. For example, on the subway, I'm down there all the time. I haven't owned a car in New York since I moved here in 1970, so I understand that most of my peers are listening in their cars, but I see kids in the subway, and they hand one earphone to their friend, and they're listening to whatever the music is, and they're only hearing half of the stereo image! (Laughs) - AND, they're still enjoying it. And I'm looking at this, with bewilderment because it's just so bizarre to me. [Guitar.com]: I found it interesting that, if you were to go to a high-end stereo store -- and I'm not even really sure such a place exists anymore.... [SK]: We don't have one here in New York City anymore. The last one we had is gone. [Guitar.com]: I used to teach guitar and I used to tell kids, "If you're having a hard time deciphering the guitar in this recording, just pan over to the left or to the right, because chances are the guitar is more on one side than the other, and you can hear better what the guitarist is playing." Then I came to realize they don't have pan knobs on modern stereos anymore. [SK]: There's no balance control? [Guitar.com]: Not on most stereos that I've seen. Kids today don't know what that is, they don't know what panning is. [SK]: Wow!!! [Guitar.com]: So if you're trying to figure out a guitar riff, and it's buried in the mix, it's really difficult. When I was learning, I knew that, "I know that guitarist is always in the left channel, so if I just pan to the left side with the balance knob, I'll be able to hear him better, and cut out most of the other instruments." But modern stereos don't have that, as far as I know. [SK]: That just seems impossible to me. [Editor's note: after we talked, Khan would send me an email saying, "I did some research on this, and you're right."] Well, what an amplifier in a home does today is more connected to -- perish the thought -- watching DVDs, playing video games, and other forms of contemporary entertainment. Music becomes almost an afterthought compared to those other options. And how the patching in the back works? It's made for surround sound, and other things, and you wonder, "Well, can't I just listen to a stereo recording any more?" [Guitar.com]: Well, let's hope when you recorded "SUBTEXT," you mixed it so perfectly no one will need a balance knob! Did you record the album mostly live? [SK]: Yes, that's always the goal. Of course, like most musicians in the Pro Tools age -- my philosophy about all of it is that you have to do what's right for the song. So if you're playing live in the studio, and you make a mistake, I think that, for the song, it's incumbent upon you to fix the error. But, in terms of creating an ambience where everybody is playing together, and everybody is relating to the music in a particular way, in the back of your mind, you always know that this option exists. The funny thing is that, sometimes you look for some form of reassurance that you can still play, and you're stuck with what you played. The double live album "THE SUITCASE," which is a trio recording with bassist Anthony Jackson and drummer Dennis Chambers, we recorded it in '94, but it didn't come out until 2008. I never thought anybody would ever want to put it out. But that was live to two-track. Sometimes when I hear that recording, I think to myself, "Well, that's really how we play." And there's virtually nothing you can fix on a recording like that. We're all very proud of what was captured on that night, the last night of long tour. [Guitar.com]: So are you playing loud in the studio? [SK]: Yes! My set-up has been the same for quite some time. When I began to have back troubles -- I used to have these two exceptionally heavy amplifiers, just the brains, for stereo, two Pearce G1s.  Eventually I had to stop using them, because the airlines were killing me with excess baggage fees. Eventually I had to stop using them, because the airlines were killing me with excess baggage fees.Then, John Abercrombie told me about the Walter Woods amps. He was one of the first guys to have a Walter Woods. So I bought an early Walter Woods, stereo amp/preamp. It's just a little thing, it could fit into your shoulder bag. But it's really powerful. So that's been my amp. I use it with the effects loop. It's very efficient for me. I wasn't always crazy about the warmth I was getting, but I've learned to work with it. [Guitar.com]: And what else are you using in the studio. I know the 335 is your main guitar. [SK]: Yes, it's the same guitar I've been using since '82. This particular guitar, from Gibson's Heritage Series, actually replaced the vintage 335 I have, because I didn't want to take that guitar on the road. This guitar, the spare, has ended up becoming the guitar that I have now played for over 30 years now. The shape of the neck is less like a club, or a baseball bat -- you know that rounded thing a lot of the old Gibson's had? That's not really best for my left hand. So this neck is more flat, not as rounded in the back. That guitar is the voice of the record. Every melody, every solo is played on that guitar. I used my ESP Strat to do these -- I call them guitar orchestrations here and there -- which I overdub, and use an Ernie Ball volume pedal with the tremolo arm added in, and I do these little swells to enhance a chord color here and there. The only other guitar that I used on the recording -- and you almost can't even hear it -- is my Martin MC-28 steel string acoustic to double a couple of passages during "Bait and Switch." On "PARTING SHOT," the Martin had a more audible role. It was just on one tune, "Zancudoville," but it had a more important function, not just as a color, doubling something. And then all of this goes out to these two Marshall bottoms, each having two 12-inch speakers inside. [Guitar.com]: Marshalls? [SK]: Yeah man! [Guitar.com]: That's pretty heavy for jazz. [SK]: How 'bout that? Like I said, a lot of people are really surprised. For example, when James Farber, the great engineer, walks into the iso booth to check the mics, or something else, he's always putting his hands over his ears. There are times when he actually has to go in there while I'm playing at full volume, and I can't turn down for his benefit. It is LOUD. It's interesting, again from an audiophile perspective, on this record, there are places in the recording where I can hear the speakers inside the Marshalls pumping. I can actually hear them. I don't know if I have ever heard it that way in the past. So we really did something in a better way this time. Sometimes you just capture things differently. But I don't think I was playing any less loud than in the past. So there you have it, that's my set-up. [Guitar.com]: Did you use the effects you list on your EQUIPMENT page on your site? [SK]: Not exactly! The truth is that I recently had my old Ibanez pedalboard reconstituted by Tom Peck, because it was falling apart. If someone asked me, "What is the secret to your sound?" I would say it's this small, 9-volt Ibanez pedal called the DCF-10, which they list as a Chorus/Flanger, but I never use the flanger part of it at all. I've written about this because people ask me about this pedal all the time, and what people can't believe is that the pedal is actually on all the time. For some reason, you only hear the chorus open up -- and I have tried to use it with more and more subtlety as the years have gone by -- when I play chords. When I play single note lines, I don't think anybody would hear the chorusing at all. So again, I have that pedal is on all the time.  Then, there are two delays, left and right, that are programmed for a ping-pong effect. When we're going to record a tune, I'll time one of side to either a quarter-note or the half note, and the other side is timed to what would be either quarter-note triplets or half-note triplets, depending on the tempo. So they're bouncing against each other. But, you never really hear it in the mix. It's mixed in at a very subtle level. But it is in there.

Then, there are two delays, left and right, that are programmed for a ping-pong effect. When we're going to record a tune, I'll time one of side to either a quarter-note or the half note, and the other side is timed to what would be either quarter-note triplets or half-note triplets, depending on the tempo. So they're bouncing against each other. But, you never really hear it in the mix. It's mixed in at a very subtle level. But it is in there. So there's some chorus, and some delay. The other sound that I use -- and I don't know how this happened -- but it appears only on the first three tunes on this record, and then never appears again. When you hear it, it sounds like my own little psychedelic big band, it is a harmonizer called the Korg DVP-1. When I was playing with Joe Zawinul in 1986, I used to sit and watch him play, especially during sound checks. It was wonderful. He used to do this thing on the Prophet synthesizer, where he would be playing/soloing, and then suddenly I'd hear what he was playing as the same voicing, but now moving in parallel. It was like music from another planet. So, I went to his keyboard tech, Ralph Skelton, and I said, "Ralphie, what is he doing when that happens?" Ralph explained, "Oh Steve, it's easy: there's a button on the Prophet called 'Unison Lock,' and the last voicing Joe played, it locks in that voicing. Then everything you play, for however long you're gonna do it, is that voicing in parallel." Ralph continued, "the problem for most people with the Prophet is that, for some reason, it tracks the lowest note in the voicing, the keyboard player's thumb on the right hand. This doesn't matter for Joe, because he's got perfect pitch, so he's hearing whatever the pinky is playing as the melody note anyway." So I said, "OK, is there anything that I could buy that would enable me to do that? I hear things that I could do, but I just don't know of a device that could give me three, four or five additional voices." And Ralph said, "Yes, there's one piece." And he told me about the Korg DVP-1. So I bought one, and I learned how to program it. The secret to what I do is this: the note that I'm actually playing is the top voice, and then I have harmonized it beneath that voice. So everything is trailing that top voice. You hear a bit of the DVP-1 on the tune, "Bird Food." You hear more of it during the fade of "Blue Subtext." In general, you could say that I use it as an orchestrational device. It appears for a final time in a couple places during "Baraka Sasa." That's really the only other effect that I used. [Guitar.com]: So it's filling in chord tones. [SK]: Yes. [Guitar.com]: I heard a guy play once at the Buffalo Niagara Guitar Festival a few years back, and he was playing solo guitar, but sounding like a Hammond organ. Do you suppose he might have been using this thing? [SK]: Well, there used to be a thing called the Guitorgan, which, when wired-up to a guitar and a Leslie speaker, can sound like an organ. [Guitar.com]: But the guy I'm thinking of was playing single note lines, but I was hearing all these harmonies, with a very organ like tone. [SK]: I think, like anything, you have to use these things judiciously. If you run it into the ground, then it is what we're calling it, an effect. It has to have a musical purpose. So as I hear its usage, when I do interject the DVP-1 into part of a phrase, there is a moment when I feel that I have my own psychedelic big band in my hands, and I can answer a particular phrase with my big band. Without this wondrous option, I would never be able to do it. [Guitar.com]: Well Steve, this has been a great and very informative conversation, and thank you so much for your time. [SK]: Thanks Adam, it was a pleasure!!!

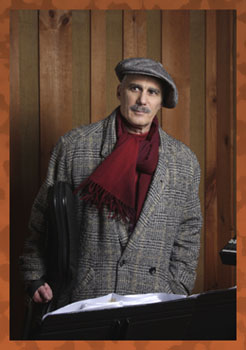

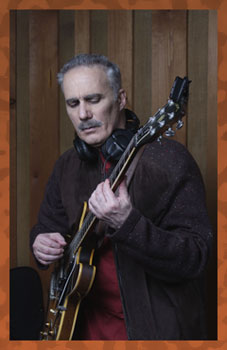

[Photos: Steve Khan @ Avatar Studios by Richard Laird]

|