|

Soundclip:

|

| See Steve's Hand-Written Solo

Transcription |

|

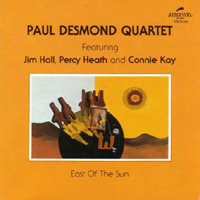

Jim Hall's solo on: "East of the Sun"(Brooks Bowman) This particular Paul Desmond Quartet recording, which featured the great Jim Hall on guitar was originally recorded in early September, 1959. The original release of "EAST OF THE SUN"(Discovery) was on Warner Bros. Records and precedes the classic RCA recordings which took place between 1963-1965. For the 1959 sessions, Desmond and Hall were joined by Percy Heath(Ac. Bass) and Connie Kay(Drums), both of whom were integral parts of the Modern Jazz Quartet. Here, I've selected Hall's 2 chorus solo over the title track, Brooks Bowman's "East of the Sun" for presentation and analysis. On this performance, Desmond plays 4 bars alone out in front, and then plays the first 16-bars of the tune without the guitar. It points out why most standards are so wonderful and hold-up well over time.  If a melody can stand alone, with only the bass for harmonic support, then it is a melody worthy of interpretation. If a melody can stand alone, with only the bass for harmonic support, then it is a melody worthy of interpretation.Over the course of my past analyses of these Jim Hall solos from this period with Paul Desmond, almost all the tunes they selected to play follow a most similar format for the solos. I don't know why one would never criticize this, but I guess it's because the playing and the familiarity of the players is so warm that it is impossible to be critical. After Desmond states the melody, as tradition would dictate, his first solo chorus is in a bare trio context only supported by Heath and Kay. Hall doesn't enter until the 2nd chorus begins. The song itself is fundamentally a variation of one of the two standards 32-bar song forms with this one falling into the [A][A'] or [A][A2] format. By using the word "variation" I mean that [A'] or [A2] contain an extra 4-bars to turn the song back around. So, this becomes the 'classic' 36-bar standard!!! Which means, be careful!!! Always listening attentively, Hall picks-up a small fragment, utilizing 'C' and Eb, from Desmond's final solo moments and then begins to weave his own tale. As he develops this solo, the interval of a 3rd returns in bars 6-9, with Ab going to 'C.' The development of motifs is always present in any Jim Hall solo. This one is no different. In Chorus 2, as [A] begins, he strings together a little idea, born of descending slurs, between bars 9-11. Then, during [A2], you see more development in bars: 1-4; and 19-20, and this idea continues as, in what would be Chorus 3, Hall and Desmond begin to duet, but Hall follows his idea through essentially until bar 9 of [A]. Though 'riding a riff' has been an important part of the Jazz tradition, this is something mostly found in the greater organ trio formats. Often times, to employ this means that the player might only have to skillfully and swingingly use a single note. If that note is well-placed, rhythmically speaking, the band will be swingin' hard! In a sense, to these ears, that's what Jim Hall does from his pick-up out of Chorus 1 into [A] of Chorus 2. Here, he rides an 'F' between bars 1-5. Then, moments later, in bars 6-8, he revisits the idea, this time using Ab. I don't know exactly why this is so, but during this particular solo, Hall employs some unusually long lines for his particular style. In Chorus 1, such lines appear during [A2] in bars: 1-5 and 14-20. In Chorus 2, further examples of this are in: bars 4-9; 11-13; and 14-16. At varying points during these longer lines, Jim Hall is utilizing a technique which he developed during these years of legato playing through eliminating picked strokes. Listen carefully to the solo and you can clearly hear these types of articulations. The reasoning is simple - less picked strokes, in most cases, serve to create more of a true 'swing.' Often times, when every note is picked, the players who employ this kind of technique tend to be a bit more stiff. It's all a matter taste, and how it is perceived by any one listener is certainly relative as well. With only 2 choruses being played, it is a little difficult to draw any fine conclusions, but Hall's treatment of certain passages is interesting to me. For example, if one views the changes in bars 13-17 of any [A2]: When you see a sequence of changes like this, you might expect the player to treat each area, each bar, with some form of the relative Dorian modes. But, it's most interesting that, both times these bars/changes appear, Hall treats the Cm7 chord with a scale passage that includes an Ab. This would seem to indicate that he might be hearing this passing chord as Aeolian? It's also, perhaps, worth noting that each time in the Dbm7-Gb7 bar, he takes a breath during the 1st half of the bar, and then plays a pick-up into the Cm7 bar. It doesn't necessarily mean anything in particular, but, it is interesting to note. Perhaps one of the reasons that some people, musicians, critics rail against Paul Desmond is the very diatonic nature of his playing. Well, that might be true. But, has there ever been a more melodic improviser than Paul Desmond? I'm not so sure that there has ever been one. So, perhaps the fact that Desmond and Hall are such sympathetic souls, is it any wonder that one can hardly find any altered tones as Hall passes from V7(alt.)-Imaj during this solo? You can hear the classic phrase with #9(Gb)-b9(Fb) over Eb7 as it cadences back to Abmaj7 in bar 16 of [A] in Chorus 1. In Chorus 2, in bar 4 over the F7 chord, Hall hits a Gb, the b9, as the chord is headed towards a resolution on Bbm7. But, in essence, that's it!!! The rest of the solo is comprised of chord tones and scale or modal tones. And yet, it's still a wonderful solo by any standards. Now that I've brought up the cadence from V7-im, I believe that it is always a good thing to address this issue in a little more detail. Players are always fighting to understand why there seem to be less options when passing to minor than there are in passing to major. In bar 4, whether it appears in [A] or [A2] of any given chorus, it is the only time in "East of the Sun" where V7, F7 in this case, is passing to im7(Bbm7).  This happens four times during Hall's solo and, of course, when Desmond and Hall begin to exchange phrases. In 4 out of 5 of the available examples in this presentation, Hall makes a point of landing on A-natural(the 3rd of F7) which is the 'leading tone' to Bbm7. That note alone sends a clear message that the cadence is coming. For one's ears, and the ears of the listener, it is more important to feature that note when going to minor than when passing to major. In the early stages of your playing and improvising, it is something you might want to take note of and then make an effort to include it. This happens four times during Hall's solo and, of course, when Desmond and Hall begin to exchange phrases. In 4 out of 5 of the available examples in this presentation, Hall makes a point of landing on A-natural(the 3rd of F7) which is the 'leading tone' to Bbm7. That note alone sends a clear message that the cadence is coming. For one's ears, and the ears of the listener, it is more important to feature that note when going to minor than when passing to major. In the early stages of your playing and improvising, it is something you might want to take note of and then make an effort to include it.Though I've mentioned this in countless other features solos here at KORNER 1, there is a particular linear configuration which usually appears over any iim7, and can also appear over the V7. When this type of line is heard many players and even scholars tend to think and say that the soloist is employing the "melodic minor" by using the major 7th tone as opposed to the b7, the more modal tone. But, to my way of thinking, it's really the usage of a chromatic lower neighbor and the implied momentary sense of the V-chord, even if it is not there! Jim Hall uses this classic line configuration in bar 6 of [A2] in Chorus 1 over the Bbm7 chord. Notice how he surrounds the root, Bb, with its consonant upper neighbor, C, and then, its chromatic lower neighbor, A-natural. You've probably heard this line 1,000,000 times, but it is an essential part of the Jazz language and therefore, everyone plays it, or even makes a special effort to avoid playing it. But, it always appears. In Chorus 2, also in bar 6 of [A2], Hall uses a C-natural before the Db as he climbs the Db Dorian mode. The C-natural appears again in bar 7 as well, except it is not configured in the same manner. In bar 7, it comes into play as part of a small arpeggio to reach the upper extensions of the chord. You could think of it as part of an Ab major triad(Ab-C-Eb) briefly used over Dbm7. In closing, though there is such an emphasis placed upon the exploration of the unexpected, the obtuse, the oblique angle when one improvises, I don't think that, in one's early development, you would not benefit greatly from being able to improvise in an almost purely diatonic fashion. And, where this is concerned, there can be no better example than Paul Desmond. Is it possible to see all the beauty in playing like this and still love the playing of John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Archie Shepp, McCoy Tyner, Joe Henderson, and countless other wonderful players? Yes, of course it is. So, don't be intimidated by those who might raise an eyebrow when the name Paul Desmond is mentioned. He is hardly a bad place to start and, no less so, a wonderful place on which to fall back!!! Jim Hall, over the course, of his long and storied career, has embraced many forms of our music and seems to be comfortable in all of them. But, his sense of melody when improvising is always on display when the recordings with Desmond are heard. So, do NOT turn your nose up at these great, great recordings!!! We have arrived at another April, and we welcome the arrival of Spring '08 with this posting. Again, I will refrain from making "Aprils Fools Day" jokes! Personally speaking I am getting very tired of all the debates and the primaries. In truth, I am very much in Barack Obama's corner. But, if Hillary Clinton was to be the nominee, I could be happy with that too. But, for me, Mr. Obama provides an inspiration, a hope, which I haven't felt since '68, and that was a long, LONG time ago.

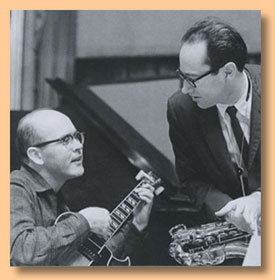

[Photo of Jim Hall and Paul Desmond by: Sue Singleton]

|