|

Soundclip:

|

| See Steve's Hand-Written Melody Statement

Transcription |

|

Jim Hall's Melody Statement of: "I'm Gettin' Sentimental Over You"(George Bassman-Ned Washington) There are certainly moments in one's life, one's professional life, when one just knows that something of great significance has taken place. Sometimes, that moment can, on the surface, appear to be relatively harmless and inconsequential. I vividly recall one such moment which took place at a rather meaningless rehearsal in the very early '70s. I had just moved to New York, and another recent transplant, the great John Abercrombie had just moved here as well. Through a number of chance encounters, we became friendly and eventually became good friends and even colleagues at times. I remember sitting together with John at this rehearsal and bemoaning the woeful quality of the music. However, because of our common roots, influences and goals, our bond in that regard was untarnished by poorly conceived music.  I will never forget how, in a moment of peace and quiet, apart from the din of '70s Jazz-Rock Fusion music, John suddenly launched into his impression of Jim Hall playing "I'm Gettin' Sentimental Over You." As simple as it was, John played that melody with such grace, love, romance and great respect, that I knew, in that moment, I was sitting next to a player who had arrived at a far deeper place in music, and within himself, than I had yet encountered. It was yet another instance when I had to face the very painful reality that I was far, far behind everyone else! During my first years in New York, there were way too many moments and realizations like that. It is a wonder that I did not go back to my hovel of a basement apartment, pack my belongings, and head back West with my tail tucked between my legs. I will never forget how, in a moment of peace and quiet, apart from the din of '70s Jazz-Rock Fusion music, John suddenly launched into his impression of Jim Hall playing "I'm Gettin' Sentimental Over You." As simple as it was, John played that melody with such grace, love, romance and great respect, that I knew, in that moment, I was sitting next to a player who had arrived at a far deeper place in music, and within himself, than I had yet encountered. It was yet another instance when I had to face the very painful reality that I was far, far behind everyone else! During my first years in New York, there were way too many moments and realizations like that. It is a wonder that I did not go back to my hovel of a basement apartment, pack my belongings, and head back West with my tail tucked between my legs.By that time, I had known most of Jim Hall's significant work with players like: Paul Desmond, Sonny Rollins, and Art Farmer, and I had even transcribed several of his solos. But, it is one thing to write out the notes, and it is yet another thing to immerse oneself in another player's soul. John Abercrombie had done that, and it showed in his own playing. He still sounded like himself, but he wore his respect for those whose playing he had admired in a wonderful way. The statement of the melody of a wonderful old standard is never as simple as it might seem on the surface. To me, it is a process involving several layers of understanding. The first layer or step, though it might seem obvious, is to fall in love with the song. In other words, you must develop a personal relationship with the song. This involves more than just learning the melody and the changes from "THE REAL BOOK" or some other songbook. Miles Davis always said, especially regarding ballads, and I am paraphrasing here, "to play a standard, it's essential to know the lyrics." I was lucky, I grew-up in home with all the great standards, and the lyrics were all around, because my father was a most resourceful and clever lyricist. So, even if, as a youngster, I didn't want to be involved with my father's music, I couldn't escape it. And now, I am so very grateful that by osmosis, or something, I know the lyrics to many, many tunes. If one is not of my generation, then you have to use your resources on the Internet and listen to several great vocal versions of the tune you seek to interpret. To whom can you turn? A short list might include the obvious: Frank Sinatra; Ella Fitzgerald; Tony Bennett; Sarah Vaughan; Nat "King" Cole; Peggy Lee; Nancy Wilson; Carmen McRae; Mel Tormé; Lou Rawls; Shirley Horn; Morgana King; and many, many others. Any of these great artists would help you to develop a feeling for the lyrics, which are married to the melodic notes and color the way the greatest players interpret these standards - no matter how abstract the interpretation might be. I am often asked at clinics, master classes, seminars, and, of course, by private students: "What is the best way to turn a 'standard' into something that 'belongs' to you?" Well, in part, I have addressed the first portion of my response in the preceding paragraph. So, please allow me to continue. I see the process for a player, young or older, as one of several steps. [1] Learn to play the melody, only in single-note lines, in your lower register first. Perhaps in a range which focuses on your 'A' and 'D'-strings and goes no higher than your 'G'-string. It should rarely touch upon your low E-string. The melody should be played over, and over, and over again until it is almost a part of your being and should exhibit great warmth and love. [2] With the 1st step completed, you would then move into your medium register and do the same process. Here, you want to keep the focus somewhere between your 'D' and 'B'-strings and hopefully not touching upon your high E-string more than is necessary. When you feel that you have really gotten everything that you can out of these steps, then you move on to [3]. Here, while playing the melody in your middle register, the register of greatest warmth of tone, in the spots where you might 'take a breath' - this is where you would begin to insert your 'guide tones' - simple two-note intervals(4ths, 5ths, or tritones) which clearly define the harmony without pushing it too hard into one period of history or another. When that is done to your satisfaction and sense of ease and comfort, you are ready for Step [4]. Here you want to attempt to personalize your harmonic colorization of the melody by placing certain harmonies under key melodic notes. This, of course, becomes a matter of instinct and personal taste. The more experience you have doing this, the easier the choices become. But, always, ALWAYS, keep in mind, that you should choose a tune because the melody is complete, just standing on its own. And that, when played as single-note lines, it can function beautifully with just a moving bass line and the propulsion of the drummer, perhaps with the lilt of the wondrous brushes?  I see this as a process which, in your early stages of doing this, could take a week or two, and perhaps even as long as a month. And then, once you actually start playing the tune with other musicians, you will be stunned at how your interpretation grows and morphs into something else - perhaps far better than you had ever imagined? After years of playing a standard, at its best, what should happen, at least in my humble opinion, is that it would begin to be the musical approximation of, for example, a Picasso line drawing in pen & ink, where the image is but an impression of what one might actually see in reality. Your personalized interpretation of a 'standard' should aspire to such artistic heights. Jim Hall's trio interpretation of "I'm Gettin' Sentimental Over You," where he is supported with warmth, swing, and subtlety by Steve Swallow: Ac. Bass; and Walter Perkins: Drums, appears on Art Farmer's wonderful and treasured 1964 recording, "LIVE AT THE HALF-NOTE." As you have no doubt already gathered from my prior remarks, I have always felt that this melody statement alone deserves to be presented here, because it embodies everything that I have been speaking about. It is simply all that you would want your own interpretation of any standard to exhibit. When you listen to this performance, now over 40 years in the past, can you hear the influence it surely had on players like: John Abercrombie; John Scofield; Pat Metheny; and Bill Frisell? It should be rather obvious! Let's take a closer look at how Jim chose to treat this lovely A-A-B-A standard. Hall's 8-bar Introduction is a model of simplicity and wonderful voice-leading. As the tune is going to be played in the key of F major, the [I] section is performed over a C-pedal. The voices move in and out of the dissonant. As one would expect there are dominant 7th sounds presented almost exclusively. However, it should be noted that in bars 2 and 6, you see a B-natural which certainly does fall into the category of a note which should not appear during any C dominant passage. However, pay attention to the voice-leading, and this will become the guiding principle. You have a small cluster with just Db and B-natural. The Db resolves upwards to a D-natural and the B-natural resolves down to a Bb. The resolution finds us at a more consonant dominant sound of C7(9/11), or some might label this chord as simply Bb/C, as I have done for the sake of simplicity. A C7(#9) chord is used to shoot us into the melody. The interpretation of the melody at both [A] and [A2] aptly demonstrates that "I'm Gettin' Sentimental Over You" is a melody which can stand on its own. And, notice the register! Perhaps it's just the fact that it is being played in this particular key, but in truth, you don't often hear 'standards' played with so much emphasis placed on one's 'A' and D-strings. Hall gracefully employs 'guide tones' in bar 4 of [A] and bars 2 and 4 of [A2]. In each case, we see the tritones, the guts of any dominant sound, to convey the sense of D7 or E7, depending upon the bar. One of the most personal and warm aspects of Jim Hall's playing is the rather slippery and slidey feel he gets from his elimination of picked strokes. You can hear this so clearly between bars 5-8 of [A] and [A2] as well. The elimination of picked strokes, as I have stated many, many times throughout the pages of this website, is what can give anyone's playing a greater sense of swing and elasticity. In my view, that's what you want! Bar 8 of [A2] is particularly Hall-esque and 'slides' us wonderfully into [B]. Yes, some m3rds appear in bar 1, and the first full chord voicing appears at the end of bar 3 into bar 4, but the melody is so rich that it can, again, stand on its own. Bars 6 through 8 demonstrate just how effective the simple 'guide tones' can be when negotiating any turnaround. Here, we pass from | E7 | Am7-D7 | Gm7-C7 || before being brought safely to resolution at [A3]. This last section, with the unusual total of 12-bars, has a twist with an additional 4 bars thrown-in. Hall marks the 'extra' turnaround with a descending sequence of 7(9) chords before hitting a D7(#9), which then resolves to a G7(13) 3-note voicing without a root. This, of course, is what I am always preaching! "Let the bass do its job, and just stay out of his way!!!" Bars 7-8 of [A3] are a perfect example of this, as each instrument and player serves its function perfectly. The melody statement concludes with a classic 2-bar "Solo Break" which Hall deftly uses to send him into the solo section. It should not be overlooked that the song's melody places such emphasis on the arpeggio, and you certainly see the outline of the basic chords in bars 1 and 3 of each [A] section. The usage of broad leaps is also most effective as you have the low B-natural up to and A-natural(the interval of a m7th) in bar 5. And then, a low Bb up to a G-natural(the interval of a maj6th). Both are most expressive and probably not particularly easy to sing. And, for those of you out there who might sometimes say: "There's not enough blues in Jim Hall's playing!" Oh? Is that so? Well, how about the end of bar 6 into bar 7 of [A2]? It might not be Albert King, but it's as playful as the 'blues' have to be! I guess I can't escape commenting on the group photo which adorned the cover of this Art Farmer LP in which Steve Swallow's eyes are half-closed. Now, it's certainly a nice photo of the two "featured artists" Farmer & Hall, but it leads one to believe that the photographer, or the LP's producer, could not find a single shot where everyone had their eyes open, or even a good facial expression. Of course, this is common when as few as two people are taking a photo. That's why, as tedious as it might be, it is important to take MANY photos, and to actually try to concentrate each time on making certain that you are getting a good shot. This photo on this LP cover is a perfect example of what happens when one is caught unaware!!! Now that 50 years have passed since this photo was taken, I'm certain that Steve only laughs when he sees it. Just recently, it came to my attention that a fantastic video performance of this very same tune exists on YouTube. Jim Hall performs here with Steve Swallow and drummer, Pete La Roca. As the camera is primarily glued to Hall and his hands, it gives you a wonderful look at how he is executing these passages on our instrument. As the song is in F major, that key, on the guitar, provides some interesting problems to be solved depending upon the register of any particular melody. This song, because it begins so low, is of particular interest. It has always been my theory that, when just hearing the audio of a performance of something on the guitar, the player is most likely to be found, as a melody or solo begins, playing near the area of one of the two most familiar chordal positions: [1] with the root on the E-string or, [2] with the root on the A-sting. In the key of F major, to try to play a melody down around the 1st fret, where your lowest 'F' exists on the E-string is going to be problematic, in general. To go up 12 frets? That's too high. So, you are left with one really good option in the middle of the instrument, which is where you would most likely choose to be anyway. Notice that Jim has chosen to be around the low 'F' at the 8th fret on his A-string and played with the pinky(4th finger) of his left-hand. Enjoy this clip, it's a great one!!! As we begin a new year, 2008, here is wishing everyone the very best of everything - especially good health! For those of us in the United States, we still have to endure one more brutal year of the George W. Bush Presidency. We should not assume that things can't get any worse, and we must be on guard for that. Having endured many brutal Republican Presidencies, this has been the absolute worst in my memory. "W." is making Nixon, and even Reagan, look 'good' by comparison!!! How horrible is that? Oh well, HAPPY NEW YEAR!!!

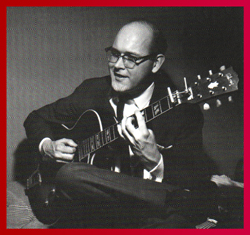

[Photo of Art Farmer-Jim Hall-Steve Swallow-Walter Perkins by: Lee Friedlander

Photo of Jim Hall by: Burt Goldblatt ] |