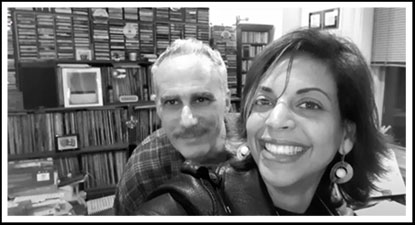

As we try our best to move away from the COVID-19 pandemic, which has occupied every aspect of our lives for just about a year-and-a-half, creative circumstances for this musician continue to appear unannounced, as if out of the blue. I have given-up trying to look skyward and inward, and then asking, "Why?" This time, the motion was created by a phone call from longtime friend, journalist Amelia Deschamps, whom I first met some 20 years ago when she was covering the Puerto Plata Jazz Festival in República Dominicana. I was there as part of the Caribbean Jazz Project. Amelia and I have remained friends since then, even if the correspondence has been most spotty at times. I've watched her career blossom in many ways, seeing her become one of the most respected and recognizable faces in the news business there. I'm very proud what she has accomplished, as it is an ever-growing list of challenges met. whom I first met some 20 years ago when she was covering the Puerto Plata Jazz Festival in República Dominicana. I was there as part of the Caribbean Jazz Project. Amelia and I have remained friends since then, even if the correspondence has been most spotty at times. I've watched her career blossom in many ways, seeing her become one of the most respected and recognizable faces in the news business there. I'm very proud what she has accomplished, as it is an ever-growing list of challenges met.

As it turned out, Amelia was wondering if I would help her out by becoming the subject for her maiden voyage into the world of podcasts. During the pandemic, I've tried to stay away from such things - the main reason being that, without a new album to promote, what is the point of answering the same old questions and telling many of the same stories/anecdotes yet again? For me, there's no point in it. But this time, because of the friendship and the added challenge of having to become the recording engineer as well, I decided to say, "Yes!" The other element that intrigued me was that, so it seemed, I wouldn't have to talk so much about myself, because she said that, after having watched and read other recent interviews, she wanted our podcast interview to be loosely based around the question: "What does Jazz sound like? What does it sound like to you?" When I heard that question during our phone conversation, I found it to be most interesting, especially philosophically. I realized that whatever kind of 'list' of artists, albums and songs that I could present from my subjective point-of-view, if one were to ask the same question of a mix of 100 great musicians and ordinary fans, the answers provided would all be quite different. However, without question, there would be certain artists that would become the thread that binds all the responses. I decided that I was going to limit what I wanted to present to music that had generally appeared between 1957 to 1968. This period of time has great personal significance because those were my late high school and college years, when every piece of music that I heard or encountered was a revelation and cause for running to my local record store in Westwood Village, near where I grew-up in Los Angeles, California. My general list would probably have to have included names like: Charlie Parker, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Ornette Coleman, Bill Evans, Herbie Hancock, John Coltrane, McCoy Tyner, Sonny Rollins, Horace Silver, Art Blakey, Wayne Shorter, Joe Henderson, Freddie Hubbard, Lee Morgan, Chick Corea, Keith Jarrett, Jimmy Smith, Larry Young, Wes Montgomery, Kenny Burrell, Jim Hall, Stanley Turrentine, Gary Burton, Cal Tjader and Bobby Hutcherson. The problem with a partial list like this is that, during any interview/podcast of about an hour in length, if you're lucky, amidst the conversation, you might be able to present, at most, 7 pieces of music, all edited down to less than 2-minutes each. So, how on earth do you choose 7 songs from a list like that? In preparation for the my conversation with Amelia, I went through my iTunes library with the number '10' in mind, and once I got started extracting songs, I couldn't stop myself, and the number actually reached 45. Impossible! The problem with a partial list like this is that, during any interview/podcast of about an hour in length, if you're lucky, amidst the conversation, you might be able to present, at most, 7 pieces of music, all edited down to less than 2-minutes each. So, how on earth do you choose 7 songs from a list like that? In preparation for the my conversation with Amelia, I went through my iTunes library with the number '10' in mind, and once I got started extracting songs, I couldn't stop myself, and the number actually reached 45. Impossible!

The conversation? Amelia arrived with some notes and questions, and prepared though I was to answer the fundamental question, I knew that the conversation would take us where it wanted to go. We decided that, as we were talking, she wanted me to insert the various songs into the Pro Tools session - in real time. Again, because I had prepared so meticulously, that was easy. In the end, there were some 11 pieces of music presented, but the conversation lasted nearly 2 hours. So, Amelia will, no doubt, be editing it all down, and so, much will have to be left out. That is the perilous nature of doing such things. But let's get back to the original question: "What does Jazz sound like?

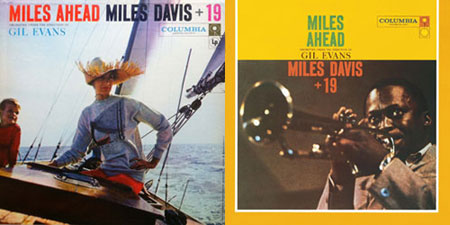

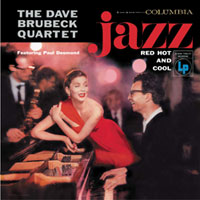

As soon as I heard that question, my thoughts were immediately transported back to those aforementioned years, late high school/early college, all in Los Angeles - University High and U.C.L.A.! I remember countless late nights, when I was supposed to be asleep, but I was actually listening to my radio - to KBCA, our Jazz station back then, and listening to the late night DJ with a pad and pencil/pen in hand, just waiting for him to tell me what I had just heard. That would then become the trigger for the next trip to the record store to buy more LPs. However, one song, and one performance of that song stuck in my mind and memory as it did then. The late night DJ had a theme song, and it would be played every night as he was being introduced. That song was the Miles Davis-Gil Evans rendering of Dave Brubeck's classic, "The Duke" - an obvious homage to the great Duke Ellington. So, in my life experience, my musical experience, my earliest moments of falling in love with Jazz, THAT song, THAT performance just said it all to me. Since then, each time that I have heard it or listened to the album "MILES AHEAD" - I am right back to being that same joyful kid learning something new at every turn.

Originally, Amelia asked me if I wanted to perform something during the podcast but, for any number of reasons, I wasn't going to do that - of course, depending upon where the conversation took us, we could always play a selection or two from one of my own recordings. However, with my thoughts and energies drifting back to "The Duke" - I listened to it several times, and allowed my imagination to begin to float within those magical notes played in 1957, and I asked myself, "I wonder what it would have felt like if I had been in the middle of that orchestra with my acoustic guitar?" And so, I embarked down that most risky of artistic, musical, and technological challenges, and I wrote out a part for myself - adjusting it along the way, and recorded my guitar. When that was completed to my relative satisfaction, I then tried to blend it in with what was there. It was strictly a linear part, no chord changes, no fills to be played - just try to be a part of the ensemble, nothing more. To simply feel the beautiful pulse of Paul Chambers (Ac. Bass) and Art Taylor's very swingin' brushes was like floating on air. Before, during and after this process, as I often do, I consulted about the audio aspects with the brilliant engineer, James Farber, who knows as much about the genre and its rich history as anyone - but he also understands all the aspects of fine hi-fi and the art of recording. He reminded me that the original LP was in MONO, and that later reissues, including not only remastered versions but horrifyingly remixed versions as well, often messed with (and I'm being polite here) the brilliance of the original recording. When I listened carefully to the version that I was playing to - which came in the Box Set, a gift from my dear sister, Laurie - right at the top, I could hear a horrible edit, as anyone with musical ears can hear that a brass stab and its ring-out had been chopped off. They were trying to begin on Bill Barber's tuba pick-up - but, even with the possibilities of slick digital editing, I don't think that you can make that edit with what was there! So, James sent me the more full version that he had. It was about 11 to 15-seconds longer, and I was able to edit it in, restoring, in part, what was once there. This was all intended to be a special surprise for Amelia's podcast debut, but having done that, I am now presenting it here along with this story. And so, I embarked down that most risky of artistic, musical, and technological challenges, and I wrote out a part for myself - adjusting it along the way, and recorded my guitar. When that was completed to my relative satisfaction, I then tried to blend it in with what was there. It was strictly a linear part, no chord changes, no fills to be played - just try to be a part of the ensemble, nothing more. To simply feel the beautiful pulse of Paul Chambers (Ac. Bass) and Art Taylor's very swingin' brushes was like floating on air. Before, during and after this process, as I often do, I consulted about the audio aspects with the brilliant engineer, James Farber, who knows as much about the genre and its rich history as anyone - but he also understands all the aspects of fine hi-fi and the art of recording. He reminded me that the original LP was in MONO, and that later reissues, including not only remastered versions but horrifyingly remixed versions as well, often messed with (and I'm being polite here) the brilliance of the original recording. When I listened carefully to the version that I was playing to - which came in the Box Set, a gift from my dear sister, Laurie - right at the top, I could hear a horrible edit, as anyone with musical ears can hear that a brass stab and its ring-out had been chopped off. They were trying to begin on Bill Barber's tuba pick-up - but, even with the possibilities of slick digital editing, I don't think that you can make that edit with what was there! So, James sent me the more full version that he had. It was about 11 to 15-seconds longer, and I was able to edit it in, restoring, in part, what was once there. This was all intended to be a special surprise for Amelia's podcast debut, but having done that, I am now presenting it here along with this story.

During the early '70s, after having just arrived here in New York, I had the distinct honor and privilege of playing in the Gil Evans Orchestra as he was mounting a kind of "comeback" to live performance - all from the cafe at the Westbeth Artists Housing Complex downtown on the West Side. It was a time when I was just as fortunate to be alternating the guitar chair with my friend, and such a great guitarist/musician, John Abercrombie. It was a fantastic experience to sit and play within that band, that collection of music, and to find my own voice inside of Gil's colors and harmonies. Each night was a wondrous learning experience - about being part of the whole, and yet allowing your voice to speak within the whole. Gil liked that - he even enjoyed the imperfections that dotted the landscapes of his charts. It is those very imperfections of phrasing, pitch and time that create Gil's sound and its impact - if music could look like a painting, it might look like something created by Salvador Dalí - I always think of and see Dalí's "melting clock" from his "The Persistence of Memory"! Like no one else, Gil's arrangements have a most evocative and haunting quality - an almost eerie nature to them - and for me, it is that very thing which makes his work so striking and enduring.

However, blending into "The Duke" was a different challenge. I found myself moving around the register of the guitar - and whether I was down the octave or up an octave, I chose what sounded and felt best to me in the context of Gil's arrangement. Without overdoing it too much, I also used my personal vibrato to express the melodic content in my way. As I went along, I revisited Dave Brubeck's original version of this classic song, and a later "live" version too, and heard that some of the arranging touches by Brubeck himself had entered into Gil's arrangement. It was beautiful to see that and to perform those touches. To have been in the middle of the big, bold brassy shouts and stabs from Gil's orchestsra was really challenging. There were also moments, because of the clustered harmonies, where I had to make a choice about which notes to go with, because it wasn't clear to me just which one was the actual melody voice. I did the best that I could with this, and I hope that you, the listener, will enjoy the choices that I made. I have included a much nicer copy of my acoustic guitar part, and anyone who decides to look at it is welcome to experience this enduring piece of music as I did. Without overdoing it too much, I also used my personal vibrato to express the melodic content in my way. As I went along, I revisited Dave Brubeck's original version of this classic song, and a later "live" version too, and heard that some of the arranging touches by Brubeck himself had entered into Gil's arrangement. It was beautiful to see that and to perform those touches. To have been in the middle of the big, bold brassy shouts and stabs from Gil's orchestsra was really challenging. There were also moments, because of the clustered harmonies, where I had to make a choice about which notes to go with, because it wasn't clear to me just which one was the actual melody voice. I did the best that I could with this, and I hope that you, the listener, will enjoy the choices that I made. I have included a much nicer copy of my acoustic guitar part, and anyone who decides to look at it is welcome to experience this enduring piece of music as I did.

On a side note, on April 2, 1959 at Studio 61 in New York. A TV program titled, The Robert Herridge Theater, normally devoted to the dramatic story-telling arts was to film Miles Davis who was joined by the Gil Evans Orchestra, and they performed 3 tunes, including "The Duke" from the 1957 "MILES AHEAD" album. Note that this presentation of Gil's arrangement begins with the tuba pick-up into an 8-bar Intro. Also of note is that Jimmy Cobb is on drums. This piece of film gives us a rare look into the feelings associated with these performances.

I must repeat myself, out of nowhere comes the inspiration to try to do something creative. In this case, there are certainly, ethical and artistic concerns about doing something/anything like this - but, I would want to believe that, as long as it is done with great love and respect for the original version and the artists involved, on all levels - perhaps it is O.K.? I'm simply going to hope so. Perhaps I can close with a note of humor in answer to the fundamental question that we started with:

This is a very old joke that I used to hear on occasion, probably back in the '70s and it went something like this....

A guy and his girlfriend were visiting New York City and trying to figure out what to do one night, and, after some thought, he said to her:

"I know, let's go hear some Jazz!"

to which his perplexed girlfriend responded quizzically......

"Jazz? Is that that music that sounds like 1,000 mice running around really fast, all at the same time, as if they don't know where they're going?!?!?!?"

To which the guy's only response was to roll his eyes and say, "Maybe we'll do something else."

|