|

Soundclip:

|

| See Steve's Hand-Written Solo

Transcription |

|

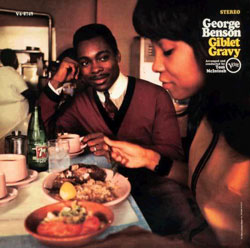

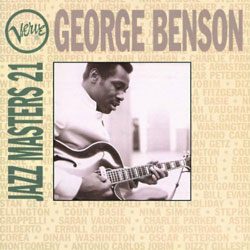

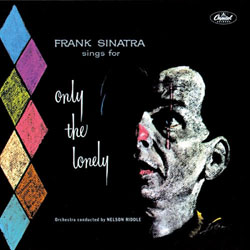

George Benson's solo on: "What's New?"(Bob Haggart-Johnny Burke) Recorded and released in early 1968, George Benson's "GIBLET GRAVY" was his first album for Verve Records under the production guidance of Esmond Edwards. His three prior recordings were all in the context of organ groups: "THE NEW BOSS GUITAR OF GEORGE BENSON"(Prestige) with Jack McDuff in 1964, and both "IT'S UPTOWN"(1966) and "COOKBOOK"(1966) with his own group for Columbia Records. "GOODIES," recorded later in 1968, again with Edwards as producer, was to be his last recording for Verve, yet, his relationship with Creed Taylor was about to begin both at A&M, and later with CTI. As I will try to explain a bit later, "What's New?" has always been a favorite ballad of mine, and it has been interpreted by practically all the great Jazz artists.  I have always loved Benson's interpretation of this tune, as it certainly represents the most Jazz-oriented approach that he was to offer on the recordings from this period. Here he appears in a quartet plus percussion setting, and is accompanied by greats such as: Herbie Hancock(Ac. Piano); Ron Carter(Ac. Bass); Billy Cobham(Drums); and Latin legend, Johnny Pacheco(Conga). This performance, and the recording quality, captures just how beautiful George's touch and tone are on the guitar, and how liquid and elastic his always blues-related phrasing can be. I have always loved Benson's interpretation of this tune, as it certainly represents the most Jazz-oriented approach that he was to offer on the recordings from this period. Here he appears in a quartet plus percussion setting, and is accompanied by greats such as: Herbie Hancock(Ac. Piano); Ron Carter(Ac. Bass); Billy Cobham(Drums); and Latin legend, Johnny Pacheco(Conga). This performance, and the recording quality, captures just how beautiful George's touch and tone are on the guitar, and how liquid and elastic his always blues-related phrasing can be."What's New?" offers the traditional song form, [A]-[A]-[B]-[A], and here, George Benson performs the ballad as something close to a Latin bolero feel, with the first [A] finding his guitar accompanied by Carter's bass and Pacheco's conga. Cobham enters lightly at [A2], with Herbie Hancock finally arriving at letter [B]. I wonder what, if any, influence Johnny Pacheco had on this rhythmic feel? Usually, when any artist, especially a great artist, interprets a standard, there will be some kind of personal stamp placed on the arrangement somewhere. Here, Benson offers a really nice touch with some alternate chord changes that appear during the [A] sections in bars 5-6. As the melody is played in 4/4, he puts a bluesier spin on the changes by passing through Cm7-F7-Bb7-Eb7 before arriving at the Ab chord, which he chooses to play as a dominant 7th type chord, Ab7(13), where others might play that same chord as Abmaj7. However, when his solo arrives, the rhythmic treatment becomes a light swing, which is felt in 2, and therefore, I decided to write out his one chorus solo in cut-time as you will see. As this album was recorded during the LP Era, there was a much greater concern for the time, the length of each song on an album. Producers endeavored to keep the total time of each side of the LP to no more than 19-minutes, with 18-minutes viewed as the ideal. The reason for this was so that in the mastering process, the pressing could be made to be as hot, loud, as was possible. A ballad can really eat-up a lot of time without even trying hard, so solo space can be at a premium. The melody statement alone, one full chorus takes about 1:35, so do the math. If George took 2 choruses, and Herbie took one, and there was a full out-head, the performance would be well over 9-minutes long! So, obviously with some thought, it was decided that George would play 1 chorus, Herbie would play a 1/2-chorus, and then Benson would rejoin at [B] with a loose interpretation of that melody, and then play the last [A]. For an ending, there would be a vamp, with George continuing to solo for a fade. It should be noted, via the reissue information, that this performance ended-up being the 3rd take of 4. The pick-up phrase that George Benson plays into this 1 chorus solo serves to really define his style and approach, even to a traditional standard. One should never forget that he came from the great blues-based organ trio, or quartet(w/ saxophone), tradition, and it has always been a natural thing to treat major 7th chords in bluesier manner. So, as we go along, take note how often you actually see him applying the degree of major 7th over Cmaj7 and Abmaj7, or Fmaj7 and Dbmaj7. In this pick-up, he's playing somewhere between a blues approach, because of the presence of the F-natural, and using the A minor pentatonic scale[A, C, D, E, G]. Though with the latter, you rarely see him use the D-natural. In bars 3-4 of [A], the ii-V to Ab major, his line is very melodic, with no alterations over the V7 chord(Eb7), and his phrasing is beautiful. When he arrives at the Abmaj7, he again applies his same most playful blues approach. Again, you see the 4th(Db), and the sense of F minor pentatonic[F, Ab, Bb, C, Eb], but here, he avoids using F and Bb. Before the iim7b5-V7 to Cm7, he takes a breath, as he uses space very well during this entire solo, which contributes greatly to the relaxed feeling throughout. In bar 8, over the G7(alt.) chord, we see one of the first virtuoso-type flurries, which highlights notes from the G altered dominant scale[G, Ab, Bb, B/Cb, Db, D#/Eb, F]. Note that you don't see Db's or F-naturals, and the root, G does not appear until the very end of the phrase. After a nice pause over the Cm7, over all the changes headed towards resolution on Ab7 he plays a sequence of triads(Ebmaj, Fm, Dbmaj, and Abmaj). Finally, to arrive at the G7(alt.) chord, he vaults up an Ebm7(9) arpeggio on beat 4 of bar 11 landing on a high F-natural for beat 1 of the G7 chord. Once again, when he cadences to Cmaj7, you see the same kind of bluesy language, and no hint of a B-natural, the major 7th degree. As this first [A] section comes to a close, in bars 15-16, the traditional iim7b5-V turnaround for this tune, heading back to a Cmaj7, you see him emphasizing both G-natural and Ab. If you look at these notes in terms of G7, you have the Root and the b9.  If you view them in terms of Dm7b5, you have the sus4 and the b5. In short, both note choices are part of either chord. If you view them in terms of Dm7b5, you have the sus4 and the b5. In short, both note choices are part of either chord.As [A2], and yet another Cmaj7 chord, arrives, George plays his bluesiest phrase yet. Here you see the blue note Eb present for the first time during this solo. I should also point out that you must pay attention to how each appearance of the 3rd(E-natural) of the maj7 chords is preceded by a grace-note slur up from D#. Some might say that this is the way to put a little soul or grease on a note like the major 3rd, that can sound so vanilla in the wrong player's hands! As the phrase ends, he anticipates the arrival of the Bbm7 chord by playing a Db, and then, taking a nice breath again. He makes a very melodic cadence to the Abmaj7 chord by playing diatonic notes, all derived from Ab major[Ab, Bb, C, Db, Eb, F, G], and in bar 4, over the Eb7 chord, you could certainly say that the notes were almost all Eb7 chord tones. The lesson here is that great playing does not always have to be the most complex linear/harmonic playing! When he arrives at the Abmaj7 in bar 5, he treats it just the same as the maj7 chords that have previously appeared. Again, notice the grace-notes before the major 3rd(C) is played. In bar 6, you see the first appearance of the degree of the major 7th(G), as he descends from C-natural. In bars 7-8, the Dm7b5 to G7(alt.) cadence to Cm7, he really treats both bars as if they were part of the G7(alt.) chord, which, of course, you can do. This becomes obvious when you see the B-natural played over the Dm7b5. In bar 8, you see a Gb, spelled that way because the line was descending, and this really is not a good note choice, even though it's a 'throw-away' note, and barely audible, it should have been an F-natural, or nothing at all, because the root, G-natural had already appeared. In bar 8, over the G7(alt.) chord, Benson begins a sequence of triplets, which accentuate important notes for any altered dominant 7th chord: Db(b5)-C-B to F(7th)-E-Eb(#5) to Bb(#9)-A-Ab(b9) resolving to G-natural over the Cm7 chord. Then he descends using the same idea: F-E-Eb to D-Db-C to F-E-Eb, and up nicely to a D-natural over the F7 chord. I suppose that this is the perfect moment to remind everyone, especially anyone who might be new to the incredible playing of George Benson, that, when playing his single-note lines, he never uses his pinky(4th finger), and does all of this with just 3 fingers on his left-hand. Honestly, even though Wes Montgomery was the same, I don't know how he does it!!! To continue, as he makes the final transition to Abmaj7, he plays another really nice melodic phrase that includes a D-natural which, relative to Ab major, is the #4 or the Lydian degree. But, as it only appears in passing, it really doesn't stick out that much. In bar 12 of [A2], with another Dm7b5 to G7(alt.), he again ignores the iim7b5 chord as he vaults up to the #9(Bb) using B(3rd)-D#(#5)-F(7th). Of course, Bb(#9) and Ab(b9) are very traditional alterations used to pull to resolution, here to another Cmaj7 chord. Once again, you never see the major 7th(B-natural), with the one inclusion of F(sus4), you still have notes from the A minor pentatonic, minus the 4th(D-natural). From there, as George makes the ii-V transition to letter [B] and Fmaj7, he plays one of his great double-time chromatic virtuoso lines. On beat 4 of bar 14, he uses the guts of Gm7, A-Bb-D-F, to vault up, à la Wes Montgomery, to A-natural, the 9th of Gm7. From there, the lines indicate that he is hearing this transition using more the sense of C7(alt.) than Gm7 for bar 15. The breathtaking descending line from his high Eb, the #9 of C7, spans 5 beats. If you look at the first note of each grouping, you see Eb(#9), then Bb(7th), Eb(#9) again, Bb(7th) again, and finally F(sus4). What strikes me as so remarkable about this passage is that he's doing it with just 3 fingers on his left-hand, so to achieve this kind of 4-note chromaticism, he has to be putting to use some very creative slurring with his left-hand. But, when we are listening, you would be hard-pressed to hear any slurring! With all these dramatics, he cadences perfectly to a C-natural on beat 1 of [B] and the Fmaj7 chord. As [B] arrives with the modulation to the IV chord, which in itself is a little unusual for standards like this, and especially because the changes mirror those found in the [A] sections, in bar 2, you see the first very traditional usage of the degree of the major 7th(E-natural) over a major 7th chord. Look at the line configuration in that bar carefully. Benson makes a very smooth transition to the Ebm7 chord by moving up 1/2-step from F-natural, the root of the prior chord, to Gb, the m3rd of the new chord. Then, we have the second appearance of a typical intervallic leap for any Jazz player, that being to jump up a major 7th, here from Gb up to F. Over that 2-bar ii-V headed towards Dbmaj7, there is no chromaticism, and all the notes are drawn from the Db major scale[Db, Eb, F, Gb, Ab, Bb, C]. I think that you will hear how this contributes to a very melodic and, in the end, cantabile or singable sensibility. Bars 5-9 of the section see him using, what I would describe as, a broken-octaves technique, as he slowly and deliberately descends chromatically from his high Ab all the way down to his landing point, a C-natural, as the Fm7 chord arrives in bar 9. As the V7 chord(Bb7) arrives, he uses another linear turn to surround his target note of Ab with both Bb above and G-natural below. It's interesting that, as he moves towards the Dbmaj7 chord in bar 11, only one tone, F-natural, is in that scale, E-natural and G-natural do not appear in the scale. From there, in bars 11-12, all the notes are related more to the sense of C7(alt.) than to Dbmaj7, even though yes, you do find Ab, Bb and C in that scale too. As he cadences to Fmaj7, you hear his first usage of the Lydian mode as a B-natural(#4) appears in bars 13 and 14. In bars 15-16, George again emphasizes both G and Ab as he did in bar 15-16 of [A], he then descends using the lower chromatic neighbors to the chord tones from G7#5, those being: G-Eb(D#)-B and G again, before cadencing with another grace-note D# to E-natural the major 3rd of Cmaj7 in bar 1 of [A3]. [A3] commences with a similar blues-based treatment to his lines, however, for the first time over this chord, he does apply the degree of the major 7th(B) at the end of bar 2. But, as the chord is about to change to Bbm7, the final note of that phrase, a C-natural, is also the 9th of Bbm7, so the presence of B-natural passes by virtually unnoticed. He then takes a breath before embarking on a 5-1/2 bar flurry of double-time 16th-notes. As I had originally done this transcription during my last couple of years('68-'69) at U.C.L.A., I decided to rewrite it, with my improved music-writing hand, and also to double-check a couple of passages with the help of Andy Robinson's brilliant program called "Transcribe!," and I know that I am now a bit closer to some reasonable degree of accuracy where the following double-time passage is concerned. It is particularly difficult because, even with technological help, some notes are obscured by the presence of Ron Carter's bass, Johnny Pacheco's conga, and Billy Cobham's bass drum. So, you might well hear something differently. The double-time passage begins at bar 3, and sees George, after that breath, playing into the Eb7 bar with a similar Montgomery-esque Bbm9th arpeggio passage involving two little Jazz phrasing mannerisms, ornaments on beats 1 and 2. On beat 1, to execute this typical horn-oriented phrase, it's so hard for me to imagine doing this without using your pinky, but he does it somehow! On beat 2, the triplet that descends down a Db triad involves a down or back-stroked sweep. As the bar comes to a close, he puts to use the traditional alterations of the #9(Gb) and b9(Fb) as part of a pattern that might sound reminiscent to some of you as related to the diminished scale. But, 1/2 of the altered dominant scale is just like a portion of the diminished scale! When Abmaj7 arrives in bar 5, he surrounds the 3rd(C) with another very traditional Jazz line configuration: Eb-Db-Bb-B-C. The key is come up to the 3rd chromatically from a whole-step below. You'll find players on all instruments using this particular linear device. From the midway point in bar 5 through the 1st half of bar 6, he descends from his C-natural on the high E-string at the 8th fret, eventually arriving at Ab(root), with the only chromaticism in this descent happening between F-E-Eb. This all makes perfect sense because he's not using his 4th finger. After an Ab triad on beat 3 of bar 6, he anticipates the coming chords Dm7b5-G7(alt.), and again, virtually ignoring the iim7b5, by playing the same line configuration that we just spoke about going from D-C-A-A#-B, surrounding the 3rd(B) of G7. In bar 7, on beat 2, the grouping of 6-notes over one beat is also a significant phrasing device, easy enough to do with a slur and one picked stroke utilizing all four fingers! But using only 3? That would certainly be tough for me. As he arrives back at the root(G), he descends, and once he arrives at the #5(Eb/D#), the line follows a very traditional route that every player in Jazz eventually learns in one form or another. At beat 3 of bar 8, he begins to make the transition to the im7 chord(Cm7), finally arriving there on beat 1 of bar 13 with a nice pentatonic line where that 1st beat sounds like G minor pentatonic(G, Bb, C, D, F) to me, because of the presence of D-natural. And this double-time flurry finally ends on the root, C-natural on beat 3. George takes another breath over the Bbm7-Eb7 in bar 10. Benson approaches the final Dm7b5-G7(alt.) cadence to Cmaj7 in bar 11 over the Ab7(13) chord with a short little triplet figure between D(b5) and F-natural(13th). This comes after some rhythmic uncertainty is resolved by his accompanists. Over bar 12, the G7(alt.) chord, he emphasizes the notes G & Ab as he has done twice before during this solo, eventually surrounding an E-natural for the resolution to Cmaj7. During bars 13-16, he treats the Cmaj7 just as he has done each time before. There are the expected bluesy references, though here he does use the blue note Eb which appears in bar 13, an F# appears in bar 14, and finally in bar 15, we have the kind of double-stop, keyboard-like interval, that we have come to expect from George Benson. He holds a C-natural on top, and plays the blues underneath it with Gb-F-Eb. It's all beautifully done with soul and grace, and he winds down in the last bars heading towards a final C-natural as he decrescendos in volume.  One last reminder, notice how he precedes the E-natural, the major 3rd of C major, with the grace note D#. If you don't learn to do such things, especially in a Jazz setting, you are going to sound very bland and ordinary! One last reminder, notice how he precedes the E-natural, the major 3rd of C major, with the grace note D#. If you don't learn to do such things, especially in a Jazz setting, you are going to sound very bland and ordinary!Perhaps it is again that time to quote Miles Davis when he said something like this: "You can never play a ballad unless you know and understand the lyrics!" For me, as the son of a lyricist, it's very hard to argue with that. Lucky for me, I grew-up in a home where all the great standards were playing on the stereo virtually all the time. So, even if I didn't want to know them, those lyrics were just engrained in my mind and psyche, and have remained there. I remember my father speaking about Frank Sinatra and his "ONLY THE LONELY" album, for which my father wrote the liner notes, and telling me that this was one of the greatest recordings ever made. Recorded in 1958, with the most spectacular arrangements by Nelson Riddle, my father always referred to this album, and the choice of material, all songs of loss and great heartbreak, as Sinatra's Ava Gardner album, as their relationship, marriage had ended in divorce in 1957. So, a song as deep and as full of emotion as "What's New?" is perfect for such an album. How great was lyricist Johnny Burke? All those incredible standards written with Jimmy Van Heusen, and then, there is this one too, written with Bob Haggart. Now, take a moment, read the lyrics, or, better yet, listen to the Sinatra version, and follow along with the lyrics. That should demonstrate, beyond any doubt why this is considered such a wonderful song, and is and will be interpreted and reinterpreted constantly. What's new? How is the world treating you? You haven't changed a bit, lovely as ever, I must admit. [A2] What's new? How did that romance come through? We haven't met since then. Gee, but it's nice to see you again. [B] What's new? Probably, I'm boring you. But seeing you is grand, and you were sweet to offer your hand I understand [A3] Adieu, pardon my asking, what's new? Of course, you couldn't know. I haven't changed, I still love you so.

Obviously, this version is told from the male perspective, so you only have to imagine what it feels like to have experienced the most painful ending of a relationship that is possible. And then, one day, totally by accident, you happen to bump into that same woman who was the great love of your life, and then, just try to imagine how awkward that conversation might be. If you can imagine that, then the story told in these deeply moving lyrics will resonate with you too. Even though George Benson's wonderful interpretation of this great standard does not take on the mournful tone of the Sinatra version, it is obvious to me that George understands everything that you need to know about this song. I'm certain that, because of the arc of his career, everyone now knows what a fantastic singer George is and always was, so lyrics should be no stranger to this great artist. |